Finding things on the internet has always been one of the main problems and promises of the worldwide web. For the last two decades, though, a single search engine, Google, has so dominated this space that its name is now the verb for “look something up online.” But history hasn’t ended, and Google has become markedly worse. For some of us, it’s time for a new search engine, and I think I may have found the one.

But first, let me back up.

Do you remember the internet of the late ’90s? That was when I first got online, and back then the main way I found stuff online were the search engines Lycos and Altavista. Those were what my dad used, so I followed his lead. My research needs were pretty simple: pictures and diagrams of castles. Generally, the search engines succeeded in turning them up for me.

In the early 2000’s, as a preteen, I started finding the limitations of these search engines. But just around that time, Google came on the scene, and I moved over with everyone else. This new search engine provided an amazing experience: finding precisely what I was looking for. Even when I just had a hunch that something specific should exist, Google would often find it for me within a few queries. It permitted a truly awesome level of granularity.

If anything, Google was too good at finding things. No longer was I randomly encountering the bizarro cruft of the internet, which had always been part of the fun of wandering around online. Even as I had this new superpower, I could feel something being lost. So I seized on the Stumbleupon browser extension (RIP) as soon as I heard about it, and as a high schooler I spent countless hours after school parachuting into random corners of the web.

But always, for search, Google.

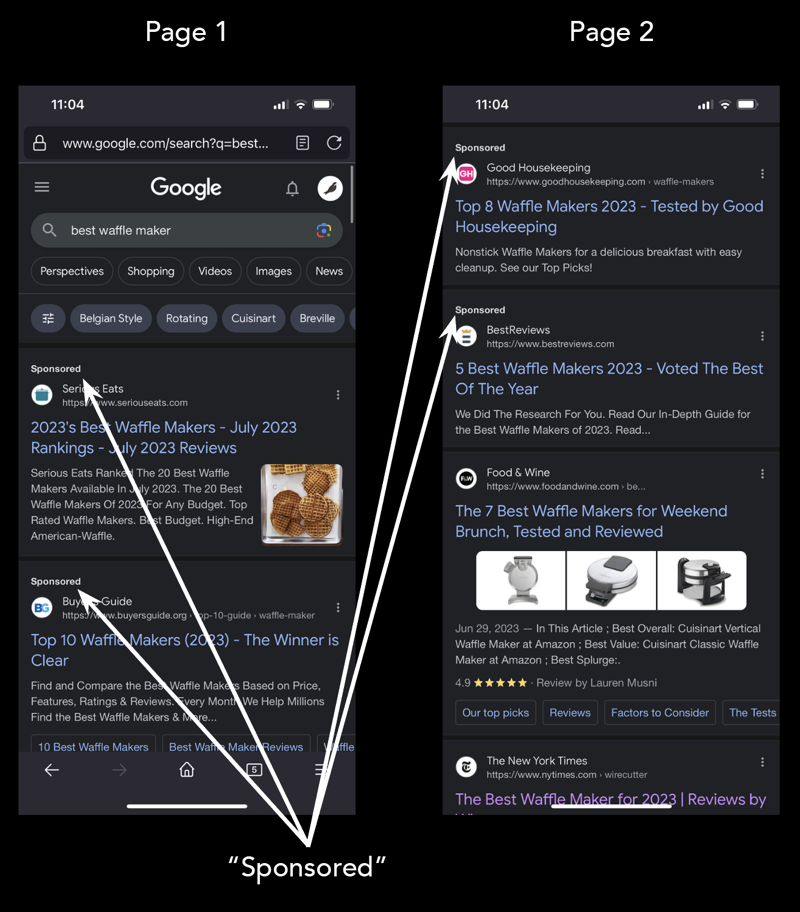

Twenty years later, though, and Google has become absolutely choked with ads. I’ve learned to pause before clicking on the first hit. No longer can I feel confident that Google has surfaced what I want. Instead, I pause and take a moment to steer around all the crap that advertisers have paid to place between me and what I’m looking for. I carefully squint to see the tiny “Sponsored” label, which seems designed to be so small and unassuming that it’ll trick me into thinking it’s a “real” search result. And it surely is designed for that exact purpose—after all, search ads are set up so that if I do click on the ad, the advertiser will pays Google $.67 (the average) or $5 or even sometimes $50 or more.

What to do about this? A few years back I tried out a search engine called Neeva for a while. (The journalist James Fallows was a big fan.) But Neeva never did the trick for me, and well before the search engine bit the dust this May, I myself abandoned it and went back to Google.

In the raft of post-mortems following Neeva’s closure, though, I heard about another pay-to-use search engine. (Via John Gruber.) This one shares with Neeva the dubious distinction of having a clumsy name—it’s called Kagi—but in every other way I think it’s better.

I’ve been using Kagi for a few months now. And I have gradually, grudgingly, come to feel that it’s a worthwhile way to spend $5 month.

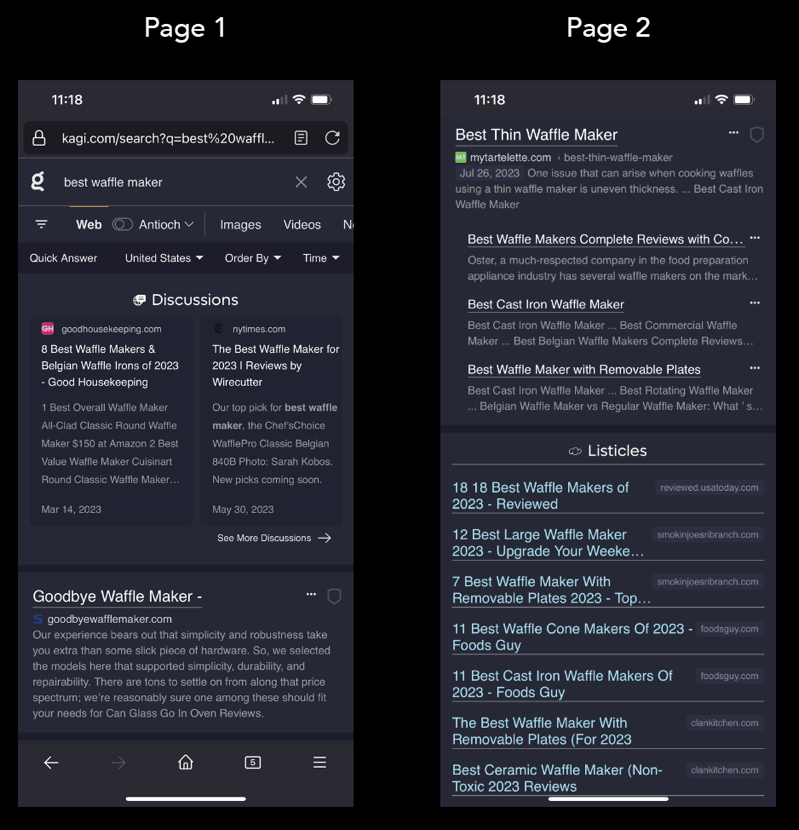

The main thing that makes Kagi leagues better than Google (2023 version) is its total lack of ads. It can’t be overstated how much of a difference it makes to use a search engine that has a business model centering your search experience rather than one premised on selling ads against your eyeballs.

At the same time, I appreciate that Kagi is not trying to be a precise but ad-free clone of Google. Instead, the team behind it seems to be working in their own way to try to make the best search engine. They provide different search filters you can customize. Results get automatically broken out into “Discussions” and “Listicles” and other useful categories. Image search becomes a gallery. There is an AI-generated summary that’s a click away for any search. And so on. There are many features I haven’t had the time or need to try yet. But basically: the Kagi team really does seem to be taking their best shot at making a great search engine.

Is it better than Google across the board? I think it’s up and down. Usually, it just works for me. Sometimes when trying to find something very specific, I do find myself having to turn back to Google. But other times I come away feeling like I wouldn’t have found the thing I ended up using, or have found it as quickly, without Kagi.

My main criticism is its pricing model, which is needlessly confusing:

The Standard plan offers 300 searches for USD $5 per month. This plan is suited for users who are new to paid search engines and are looking to own their search experience.

The Professional plan offers 1,000 searches for USD $10 per month. This plan is suited for internet professionals and developers who are prolific and advanced search users.

…

Pay Per Use Enhancement

The Standard and Professional plans both feature Pay Per Use options within the Billing Settings. Searches beyond the monthly included searches, are priced at 1.5 cents per search. There are two limits that you can set to control your cost:

• The soft limit triggers a notification regarding pay-per-use cost

• The hard limit prevents further searches so you do not incur additional costs.

That is so confusing and arcane. And worse, pay-per-search makes it seem like you should be miserly with actually using Kagi. Do they really want to incentivize users to not use their tool?

Happily, I can report that even if you think you use search all the time, you should just select the $5/month version and continue on your merry way. I have yet to hit their limits, and even if I do, they’ll just charge me a few bucks extra that month. Whatever.

The biggest, best thing about Kagi has been feeling my muscle memory shift back to an earlier, less defensive way of being. I have slowly shed my instinctive distrust of the first result. I don’t find myself looking for those little “sponsored” tags. And consequently, search has become less of a chore, less of a hassle, and more of a pleasure.

Sophomore year of college, I figured out that the university library’s card catalogs had been shoved into an old hallway and were still accessible, despite having been replaced years before by a digital catalog. I would sometimes go and browse the contents of these handsome old walnut cabinets for twenty minutes or an hour, looking up my current interests and seeing what titles I might find adjacent, and what further notes I might find on the cards. It was curiously satisfying. A few times, I did find a book that I’d go chase down in the stacks, but more often I just enjoyed surveying the titles and keywords and generally getting the intellectual lay of the land.

Kagi isn’t as inefficient as that old card catalog. It’s a fully functional search engine of the ’20s. But using it does have some of the same feeling of engaging with information in an older, less adversarial way. You pay $5, and in return you aren’t subjected to Google’s intrusive surveillance ad-tech and in-your-face ads. Google, by contrast, pockets $21/month/user, mostly from ads.

The big takeaway? Kagi is a search engine that doesn’t make you feel like you are the ore in an elaborate mining operation. Instead, a bit surprisingly, it feels like a small gift to yourself.